മുന്നിലേയ്ക്കുള്ള മഹത്തായ കുതിച്ചുചാട്ടം

| History of the People's Republic of China (PRC) |

|---|

|

| History of |

| Generations of leadership |

| മുന്നിലേയ്ക്കുള്ള മഹത്തായ കുതിച്ചുചാട്ടം | |||||||||||||||||||||

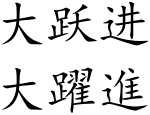

"മുന്നിലേയ്ക്കുള്ള മഹത്തായ കുതിച്ചുചാട്ടം" ലഘൂകരിച്ച ചൈനീസ് (മുകളിൽ) പരമ്പരാഗത ചൈനീസ് (താഴെ) അക്ഷരങ്ങൾ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 大跃进 | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 大躍進 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | "മുന്നിലേയ്ക്കുള്ള കുതിച്ചുചാട്ടം" | ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

പീപ്പിൾസ് റിപ്പബ്ലിക് ഓഫ് ചൈനയിൽ ചൈനീസ് കമ്യൂണിസ്റ്റ് പാർട്ടി നടപ്പിലാക്കിയ ഒരു സാമൂഹിക പദ്ധതിയാണ് മുന്നിലേയ്ക്കുള്ള മഹത്തായ കുതിച്ചുചാട്ടം (ചൈനീസ്: 大跃进; പിൻയിൻ: Dà yuè jìn) എന്നറിയപ്പെടുന്നത്. 1958 മുതൽ 1961 വരെയാണ് ഇത് നടപ്പിലാക്കിയത്. മാവോ സെതുങ്ങിന്റെ നേതൃത്ത്വത്തിലായിരുന്നു ഇത് നടപ്പിലാക്കിയത്. രാജ്യത്തെ ഒരു കാർഷിക സാമ്പത്തിക വ്യവസ്ഥയിൽ നിന്ന് വ്യവസായവത്കരണത്തിലൂടെയും കളക്റ്റീവുകളിലൂടെയും സോഷ്യലിസ്റ്റ് സമൂഹമാക്കി പെട്ടെന്ന് മാറ്റിയെടുക്കുക എന്നതായിരുന്നു ഈ പദ്ധതിയുടെ ഉദ്ദേശം. ചൈനയിലെ വലിയൊരു പട്ടിണിയിലേയ്ക്കാണ് ഈ പദ്ധതി നയിച്ചത്.

കൂട്ടുകൃഷി സമ്പ്രദായം നടപ്പിലാക്കിയും സ്വകാര്യ കൃഷി നിരോധിച്ചും മറ്റുമാണ് ഈ പദ്ധതി മുന്നോട്ട് പോയത്. സ്വകാര്യ കൃഷി ചെയ്തവരെ വേട്ടയാടുകയും അവരെ പ്രതിവിപ്ലവകാരികളായി മുദ്രകുത്തുകയും ചെയ്തു. ഗ്രാമീണരെ സാമൂഹികമായ സമ്മർദ്ദത്തിലൂടെ നിർബന്ധിച്ച് പണിയെടുപ്പിക്കുമായിരുന്നു. പണിയെടുക്കാൻ ബലം പ്രയോഗിക്കുന്ന സാഹചര്യവും നിലനിന്നിരുന്നു. [1] ആദ്യകാലത്ത് ഗ്രാമീണ വ്യവസായവൽക്കരണം വികസിച്ചുവെങ്കിലും പിന്നീട് തകർന്നുപോയി.[2]

ഈ പദ്ധതിയുടെ ഭാഗമായി കോടിക്കണക്കിനാൾക്കാർ പട്ടിണി മൂലം മരിച്ചു എന്നത് പൊതുവിൽ അംഗീകരിക്കപ്പെട്ട വസ്തുതയാണ്.[3] 1.8 കോടി മുതൽ 3.25 കോടി വരെയും[4] 4.6 കോടിവരെയുമുള്ള വ്യത്യസ്തമായ കണക്കുകളാണ് ഇതുസംബന്ധിച്ചുള്ളത്.[5] മനുഷ്യരുടെ ചരിത്രത്തിൽ തന്നെ ഏറ്റവും വലിയ കൂട്ട മരണത്തിലേയ്ക്കാണ് ഇത് വഴിവച്ചതെന്ന് നിരീക്ഷിക്കപ്പെട്ടിട്ടുണ്ട്.[6] ഇക്കാലത്ത് ചൈനയുടെ സാമ്പത്തികരംഗം ചുരുങ്ങുകയാണുണ്ടായത്.[7] വലിയ മുതൽ മുടക്കിൽ നിന്നും വളരെച്ചെറിയ വരവേ ഉണ്ടായിരുന്നുള്ളൂ[8]

പിന്നീട് ഈ പദ്ധതിയുടെ ദോഷവശങ്ങളെക്കുറിച്ച് (1960 മാർച്ചും 1962 മേയ് മാസവും) ചൈനീസ് കമ്യൂണിസ്റ്റ് പാർട്ടി ചർച്ചകൾ നടത്തുകയുണ്ടായി. സമ്മേളനങ്ങളിൽ മാവോയെ കുറ്റപ്പെടുത്തപ്പെട്ടു. മിതവാദികളായ ലിയു ഷവോക്വി, ഡെങ് സിയാവോപിങ് എന്നിവർ നേതൃത്വനിരയിലേയ്ക്കുയർന്നു. മാവോയെ പാർട്ടിക്കുള്ളിൽ ഒറ്റപ്പെടുത്തപ്പെട്ടു. 1966-ൽ മാവോ സാംസ്കാരിക വിപ്ലവം എന്ന പദ്ധതി പ്രഖ്യാപിക്കുന്നതിലേയ്ക്കാണ് ഇത് നയിച്ചത്.

മാവോയെ അനുകൂലിക്കുന്നവർ മരണസംഖ്യ ചോദ്യം ചെയ്യുന്നുണ്ട്. പട്ടിണിമരണങ്ങൾ ഈ പദ്ധതി മൂലമല്ല ഉണ്ടായതെന്നും [9] ഇത് വ്യവസായ വൽക്കരണത്തിലേയ്ക്ക് നയിച്ചുവെന്നും അവർ അവകാശപ്പെടുന്നു.

സാമ്പത്തിക പ്രത്യാഘാതങ്ങൾ

[തിരുത്തുക]പദ്ധതിയുടെ ആദ്യ നാളുകളിൽ ചൈനയുടെ സാമ്പത്തികരംഗത്ത് വളർച്ചയാണുണ്ടായത്. ഇരുമ്പിന്റെ ഉത്പാദനം 1958-ൽ 45 ശതമാനം വർദ്ധിച്ചു. 1961-ൽ ഇടിഞ്ഞ ഉത്പാദനം 1964-ലാണ് വീണ്ടും 58-ലെ സ്ഥിതിയിലെത്തിയറ്റ്. 30 മുതൽ 40% വരെ വീടുകൾ തകർക്കപ്പെട്ടു.[10] ഗ്രാമവാസികളെ മാറ്റിത്താമസിക്കാനും വളമുണ്ടാക്കാനും റോഡുകൾ ബലപ്പെടുത്താനും ഭക്ഷണശാലകൾ പണിയാനും മറ്റും വീടുകൾ പൊളിക്കുകയായിരുന്നു ചെയ്തത്. ചിലപ്പോൾ വീട്ടുടമസ്ഥരെ ശിക്ഷിക്കാനായിരുന്നു വീടുകൾ പൊളിക്കപ്പെട്ടത്.[11]

1960-കളിൽ കൂട്ടുകൃഷി ക്രമേണ ഉപേക്ഷിക്കപ്പെട്ടു. ആദ്യകാലത്ത് കർഷകരെ സഹായിക്കുവാൻ ഗവണ്മെന്റിന് സാധിച്ചില്ല. പക്ഷേ 1960-കളിൽ കുറഞ്ഞ തോതിലും പിന്നീട് ഡെങ് സിയാവൊ പിങിന്റെ ഭരണകാലത്ത് 1978-ന് ശേഷവും കർഷകരുടെ സാമ്പത്തികസ്ഥിതി വളരെ മെച്ചപ്പെട്ടു.[12] തങ്ങളുടെ ഭാവിക്ക് ഭീഷണിയുണ്ടായിട്ടുപോലും ചില കമ്യൂണിസ്റ്റ് പാർട്ടി അംഗങ്ങൾ പാർട്ടി നേതൃത്ത്വത്തിനെയാണ് പദ്ധതിയുടെ പരാജയത്തിന് കുറ്റം പറഞ്ഞത്. സാമ്പത്തികരംഗം വികസിപ്പിക്കുന്നതിന് സാങ്കേതികജ്ഞാനം വികസിപ്പിക്കുകയും ബൂർഷ്വാകളുടെ രീതികൾ സ്വീകരിക്കുകയും ചെയ്യണമെന്ന് പലരും വാദിച്ചു. ലിയും ഷവോക്വി 1962-ലെ സമ്മേളനത്തിൽ സാമ്പത്തികത്തകർച്ചയുടെ 30% കാരണം പ്രകൃതിയും, 70% മനുഷ്യന്റെ പിഴവുകളുമാണെന്നായിരുന്നു.[13]

എതിർത്തുനിൽപ്പുകൾ

[തിരുത്തുക]പലതരത്തിൽ ജനങ്ങൾ മുന്നിലേയ്ക്കുള്ള മഹത്തായ കുതിച്ചുചാട്ടത്തെ എതിർത്തു. പല പ്രവിശ്യകളിലും സായുധകലാപമുണ്ടായി.[14][15] ഈ കലാപങ്ങളൊന്നും കേന്ദ്രഗവണ്മെന്റിന് വലിയ ഭീഷണിയുയർത്തിയില്ല.[14] ഹെനാൻ, ഷാങ്ഡോങ്, ക്വിങ്ഹായ്, ഗാൻസു, സിച്ചുവാൻ, ഫുജിയാൻ, യുന്നാൻ, ടിബറ്റ് എന്നിവിടങ്ങളിൽ കലാപമുണ്ടായി.[16][17] പാർട്ടി അംഗങ്ങൾക്കെതിരേ പലയിടത്തും ആക്രമണങ്ങളുമുണ്ടായി.[15][18] ധാന്യപ്പുരകൾ പലയിടത്തും ആക്രമിക്കപ്പെട്ടു. [15][18] ട്രെയിൻ കൊള്ളകളും അടുത്തുള്ള ഗ്രാമങ്ങൾ ആക്രമിച്ച് കൊള്ളയടിക്കലും മറ്റും സാധാരണമായിരുന്നു.[18]

ഇതും കാണുക

[തിരുത്തുക]- Ryazan miracle

- The Black Book of Communism

- Virgin Lands Campaign, contemporary program in the Soviet Union

അവലംബം

[തിരുത്തുക]- ↑ Mirsky, Jonathan. "The China We Don't Know." New York Review of Books Volume 56, Number 3. February 26, 2009.

- ↑ Perkins, Dwight (1991). "China's Economic Policy and Performance". Chapter 6 in The Cambridge History of China, Volume 15, ed. by Roderick MacFarquhar, John K. Fairbank and Denis Twitchett. Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Tao Yang, Dennis (2008). "China's Agricultural Crisis and Famine of 1959–1961: A Survey and Comparison to Soviet Famines." Palgrave MacMillan, Comparative Economic Studies 50, pp. 1–29.

- ↑ Gráda, Cormac Ó (2011). "Great Leap into Famine". UCD Centre For Economic Research Working Paper Series: 9.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Dikötter, Frank. Mao's Great Famine: The History of China's Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958–62. Walker & Company, 2010. p. xii ("at least 45 million people died unnecessarily") p. xiii ("6 to 8 percent of the victims were tortured to death or summarily killed—amounting to at least 2.5 million people.") p. 333 ("a minimum of 45 million excess deaths"). ISBN 0-8027-7768-6.

- ↑ Dikötter, Frank (2010). pp. x, xi. ISBN 0-8027-7768-6

- ↑ "ആർക്കൈവ് പകർപ്പ്". Archived from the original on 2013-07-16. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

- ↑ Perkins (1991). pp. 483–486 for quoted text, p. 493 for growth rates table.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Dikötter (2010). p. 169.

- ↑ ഉദ്ധരിച്ചതിൽ പിഴവ്: അസാധുവായ

<ref>ടാഗ്;Dikötterxiഎന്ന പേരിലെ അവലംബങ്ങൾക്ക് എഴുത്തൊന്നും നൽകിയിട്ടില്ല. - ↑ Woo-Cummings, Meredith Archived 2013-11-29 at Archive.is (2002). "The Political Ecology of Famine: The North Korean Catastrophe and Its Lessons" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-03-18. Retrieved 2016-11-18. (807 KB), ADB Institute Research Paper 31, January 2002. Retrieved 3 Jul 2006.

- ↑ Twentieth Century China: Third Volume. Beijing, 1994. p. 430.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Dikötter (2010) pp. 226–228.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Rummel (1991). pp. 247–251.

- ↑ Dikötter (2010) pp. 226–228 (Qinghai, Tibet, Yunnan).

- ↑ Rummel (1991). pp. 247–251 (Honan, Shantung, Qinghai (Chinghai), Gansu (Kansu), Szechuan (Schechuan), Fujian), p. 240 (TAR).

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Dikötter (2010) pp. 224–226.

- This article incorporates public domain text from the United States Library of Congress Country Studies. – China

ഗ്രന്ഥസൂചിക

[തിരുത്തുക]- Ashton, Hill, Piazza, and Zeitz (1984). Famine in China, 1958–61. Population and Development Review, Volume 10, Number 4 (Dec., 1984), pp. 613–645.

- Bachman, David (1991). Bureaucracy, Economy, and Leadership in China: The Institutional Origins of the Great Leap Forward. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- [Bao] Sansan and Bette Bao Lord (1964). Eighth Moon: The True Story of a Young Girl's Life in Communist China, New York: Harper & Row.

- Becker, Jasper (1998). Hungry Ghosts: Mao's Secret Famine. Holt Paperbacks. ISBN 0-8050-5668-8

- Jung Chang and Jon Halliday. (2005) Mao: The Unknown Story, Knopf. ISBN 0-679-42271-4

- Dikötter, Frank (2010). Mao's Great Famine: The History of China's Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958–62. Walker & Co. ISBN 0-8027-7768-6

- Gao. Mobo (2007). Gao Village: Rural life in modern China. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3192-9

- Gao. Mobo (2008). The Battle for China's Past. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-2780-8

- Li. Minqi (2009). The Rise of China and the Demise of the Capitalist World Economy. Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-182-5

- Li, Wei; Tao Yang, Dennis (2005). "The Great Leap Forward: Anatomy of a Central Planning Disaster". Journal of Political Economy. 113 (4): 840–877. doi:10.1086/430804.

- Li, Zhisui (1996). The Private Life of Chairman Mao. Arrow Books Ltd.

- Macfarquhar, Roderick (1983). Origins of the Cultural Revolution: Vol 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Short, Philip (2001). Mao: A Life. Owl Books. ISBN 0-8050-6638-1

- Tao Yang, Dennis. (2008) "China's Agricultural Crisis and Famine of 1959–1961: A Survey and Comparison to Soviet Famines." Palgrave MacMillan, Comparative Economic Studies 50, pp. 1–29.

- Thaxton. Ralph A. Jr (2008). Catastrophe and Contention in Rural China: Mao's Great Leap Forward Famine and the Origins of Righteous Resistance in Da Fo Village. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-72230-6

- Wertheim, Wim F (1995). Third World whence and whither? Protective State versus Aggressive Market. Amsterdam: Het Spinhuis. 211 pp. ISBN 90-5589-082-0

- E. L Wheelwright, Bruce McFarlane, and Joan Robinson (Foreword), The Chinese Road to Socialism: Economics of the Cultural Revolution.

- Yang, Dali (1996). Calamity and Reform in China: State, Rural Society, and Institutional Change since the Great Leap Famine. Stanford University Press.

- Yang, Jisheng (2008). Tombstone (Mu Bei - Zhong Guo Liu Shi Nian Dai Da Ji Huang Ji Shi). Cosmos Books (Tian Di Tu Shu), Hong Kong.

- Yang, Jisheng (2010). "The Fatal Politics of the PRC's Great Leap Famine: The Preface to Tombstone". Journal of Contemporary China. 19 (66): 755–776. doi:10.1080/10670564.2010.485408.

പുറത്തേയ്ക്കുള്ള കണ്ണികൾ

[തിരുത്തുക]- Ball, Joseph. Did Mao Really Kill Millions in the Great Leap Forward? Archived 2019-10-11 at the Wayback Machine.. Monthly Review. September 21, 2006

- Chinese Government’s Official Web Portal (English). China: a country with 5,000-year-long civilization.

- Damiani, Matteo A tragic episode of cannibalism during the famine of the Great Leap Forward Archived 2019-02-07 at the Wayback Machine.. November 2012.

- Dikotter, Frank. Mao's Great Leap to Famine, New York Times. December 15, 2010.

- Johnson, Ian. Finding the Facts About Mao’s Victims. The New York Review of Books (Blog), December 20, 2010.

- McGregor, Richard. The man who exposed Mao’s secret famine. The Financial Times. June 12, 2010.

- Meng, Qian, and Yared (2010) The Institutional Causes of China's Great Famine, 1959-1961 Archived 2019-09-06 at the Wayback Machine. (pdf).

- Wagner, Donald B. Background to the Great Leap Forward in Iron and Steel University of Copenhagen. August 2011.